Which word class do 'possessive' words belong to?

Adjectives, determinatives or pronouns?

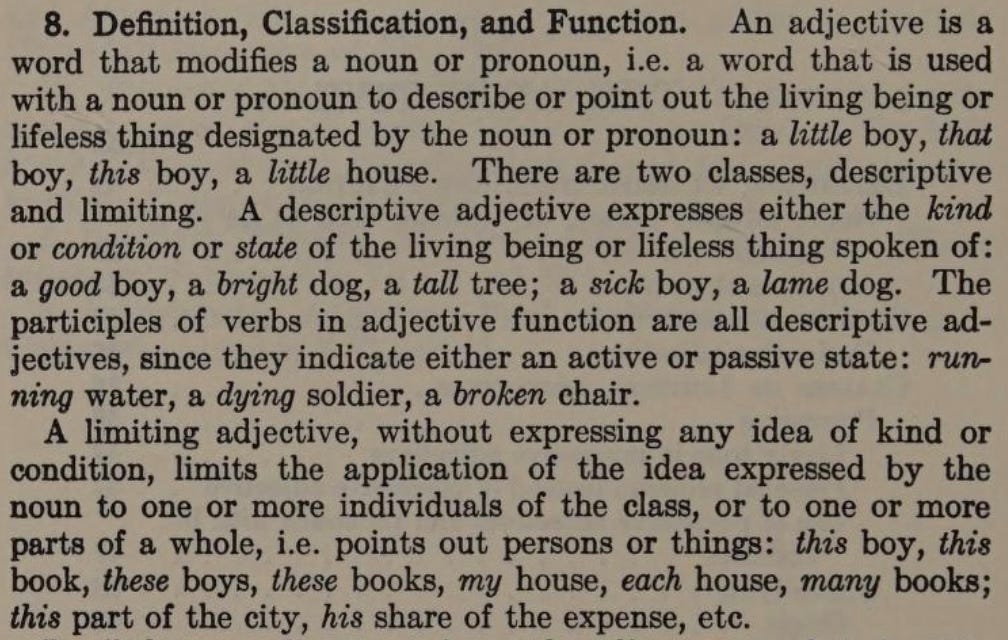

In his 1931 book Parts of Speech and Accidence, the American grammarian George Curme distinguished two types of adjectives: descriptive adjectives and limiting adjectives:

In later sections of his book Curme describes the limiting adjectives in more detail: words like this, these, that, those, each, many, etc. are labelled demonstrative adjectives, while my, your, his, her, our, etc. are called possessive adjectives.

But are these words really adjectives?

To answer this question we first need to ask how we can define the word class of adjective. What are the grammatical characteristics of adjectives?

We can say that typical adjectives conform to the following criteria:

They can modify nouns by ascribing a property to them in an attributive position: She has a bright future.

They can be placed after verbs such as be, seem, appear, etc. in predicative position: The future seems bright.

They can be modified by words like very or extremely: The future is very/extremely bright.1

They can be changed into comparative or superlative forms: brighter, brightest.

A small subset of adjectives can take the prefix un-/in-, e.g. unhappy, inclement, etc.

We can agree with Curme that words like this, these, that, and those have a ‘limiting’ or ‘specifying’ function. So, for example, when I talk to you about this bicycle I’m referring to a specific bicycle in our vicinity, namely the one I’m pointing at. Words like this, these, that and those are said to be deictic (from the word for ‘point’ or ‘show’ in ancient Greek). In other words, in the case of this particular example, such words help us to identify the bicycle the speaker is referring to.

However, you may remember that in a previous post I classed words like a, the, this, these, that, and those as determinatives, not as adjectives.

Why?

Semantically, words like this, these, that and those do not behave like adjectives, because they do not ascribe a property to the noun they are placed with, in the way that adjectives do. Instead, as we have just seen, their job is ‘specify’ the meaning of the noun more precisely.

Grammatically, these words do not behave as adjectives either, because none of the criteria listed above apply to them, apart from their position in front of nouns. So while we can talk about this bicycle, we can’t say *The bicycle is this. We also can’t say *very this, *very those, etc., and these words do not have comparative and superlative forms.

What about the ‘possessive’ words my, your, his, her, etc.? These words are typically dependent on a following noun. They mostly don’t occur on their own.2

As we have seen, Curme regards them as possessive adjectives. And this is also a label you will see in many practically-oriented grammar books and websites. However, the label is wrong. There’s no such thing as a possessive adjective, as I have previously argued in a Grammarianism post.

The dependent ‘possessives’ do not behave as adjectives for the same reasons that this, these, that, those do not behave as adjectives. You’ll see why when you try to apply the adjective criteria shown above.

But if they are not adjectives, what are they? There are two remaining possibilities: they could be determinatives or pronouns.

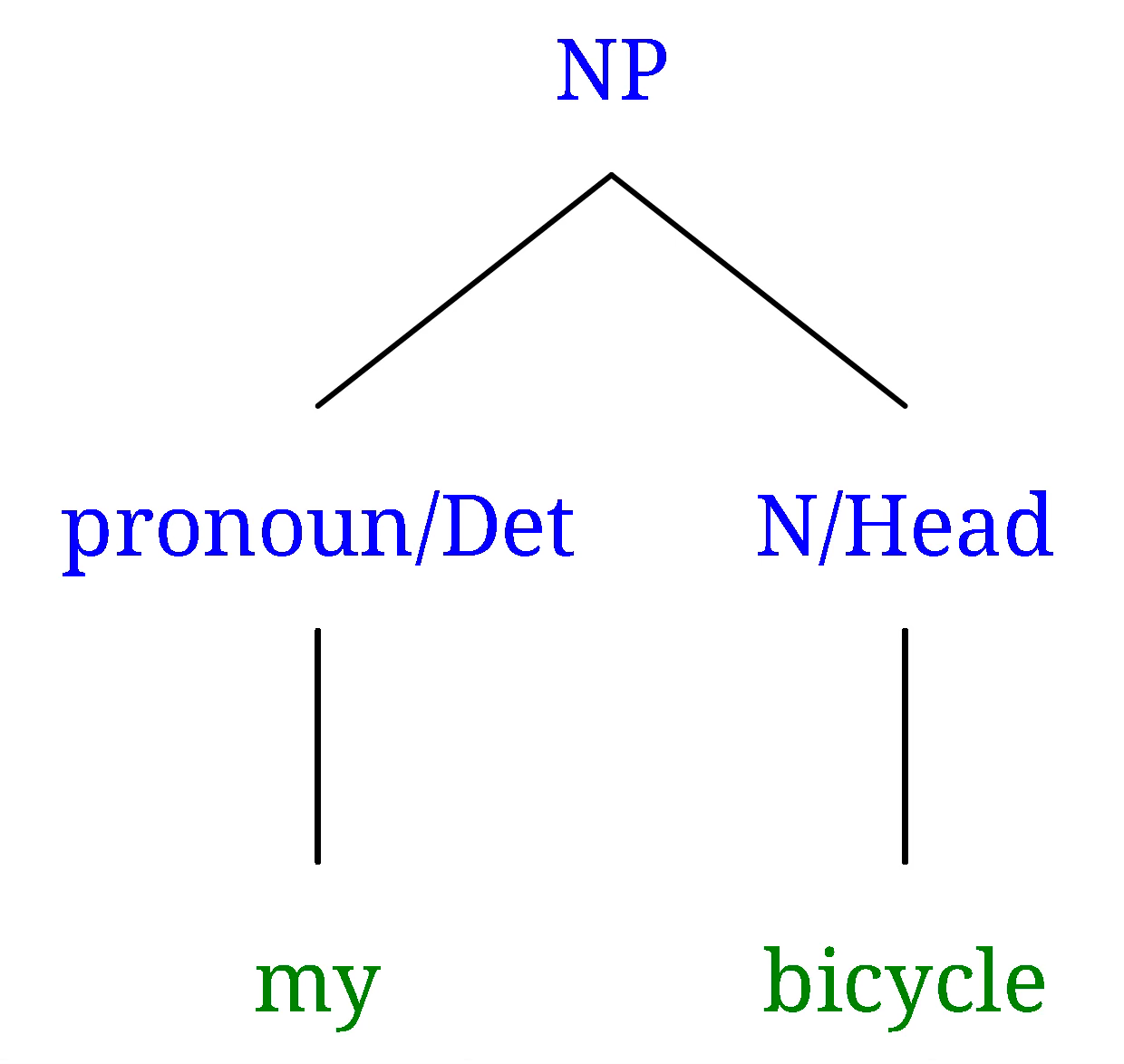

In the noun phrase my bicycle, could my be a determinative? Maybe, because one could say that my limits the reference of the noun bicycle, in the way that determinatives do. After all, it refers to a specific, identifiable bicycle: the one that belongs to me. However, the idea is not tenable, because the word my has a grammatical property that does not apply to determinatives: it has genitive case.3

So it seems that the best solution is to say that ‘possessive’ words such as my, your, his, her, etc. belong to the word class of pronouns.

But we’re not quite there yet. We also need to assign a grammatical function label to these words in particular structures. In my bicycle the most obvious function label for my is Determiner. (See my earlier post for a discussion of this label.) Now we can represent the structure of the noun phrase my bicycle as follows:45

Recall that in such tree diagrams each element is assigned a grammatical form label and a grammatical function label.

What about the ‘possessive’ lexical items mine, yours, his, hers, etc., as in:

That bicycle is mine.

Here mine is an independently occurring pronoun in the genitive case. And because pronouns are a subclass of nouns, this word is also a noun. It functions as the Head of a noun phrase:

[NP This bicycle] is [NP mine].6

The treatment of dependent and independent genitive pronouns is often confusing and inconsistent in grammars, textbooks and on websites.

For example, Quirk et al. (1985: 256) label words like my, your, his, etc. as “possessive pronouns [used] as determiners.” But this is problematic, because for Quirk et al. pronoun and determiner are both word class labels, so that in their analysis of my in my bicycle they are simultaneously assigning this word to two word classes. However, it is a generally accepted principle of grammar that in any particular construction a word cannot belong to two word classes at the same time.7

And here’s a British Council website on ‘possessive adjectives’.

Finally, let’s briefly return to Curme’s work, cited above. The eagle-eyed among you will have spotted that Curme lists many as an adjective. As my earlier post about this word makes clear, I think he was right about that!

References

Curme, George O. (1931) Parts of Speech and Accidence. Boston: D.C. Heath and Co.

Huddleston, Rodney and Geoffrey Pullum (2002) The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech and Jan Svartvik (1985) A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.

In the third example very/extremely bright is clearly an adjective phrase. But be aware that this is also the case for bright in the first two examples, since we can add very in front of it: She has [NP a [AdjP very bright] future]; The future seems [AdjP very bright].

There are exceptions, namely when words like my occur as the Subject of a clause: He was angry about [my being very impolite to our guests].

The main cases in English are nominative case (I, he, she, we, etc.), accusative case (me, him, her, us, etc.) and genitive case (my, his, her, our, mine, hers, his, ours, etc.). Instead of these Latin-derived names sometimes you find alternative labels: subjective case, objective case.

Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 471f.) claim that my in my bicycle has the function not just of Determiner, but Subject-Determiner, by analogy with e.g. my analysis, where we can say that ‘I made an analysis’. I don’t find this convincing.

Strictly speaking, because pronouns are nouns, my is not just a pronoun, but also a noun phrase.

Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 471) have a more complex analysis: they assign the function label fused Subject-Determiner-Head to independent genitive NPs like mine.