"What the hell is a determiner?"

Demystifying a relatively new word class

"What the hell is a determiner?"

This was the question posed in a tweet at the time when the grammar specifications of the National Curriculum for England were published in 2014 for young children at primary school age (6-12).

It was not an untypical response, and also not an unreasonable one. The word class of determiner is a relatively recent one, and the first use of this label is often attributed to the American linguist Leonard Bloomfield (who lived from 1887 to 1949). It has been used widely in modern linguistics since that time, but didn’t make its way into practical grammars and teaching materials.

Before we move on I want to introduce an important terminological change.

From now on I will use determinative as a word class label, and determiner as a function label. This is in line with the Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, which introduced this practice. (I will return below to the label determiner as a grammatical function.)1

So what is a determinative?

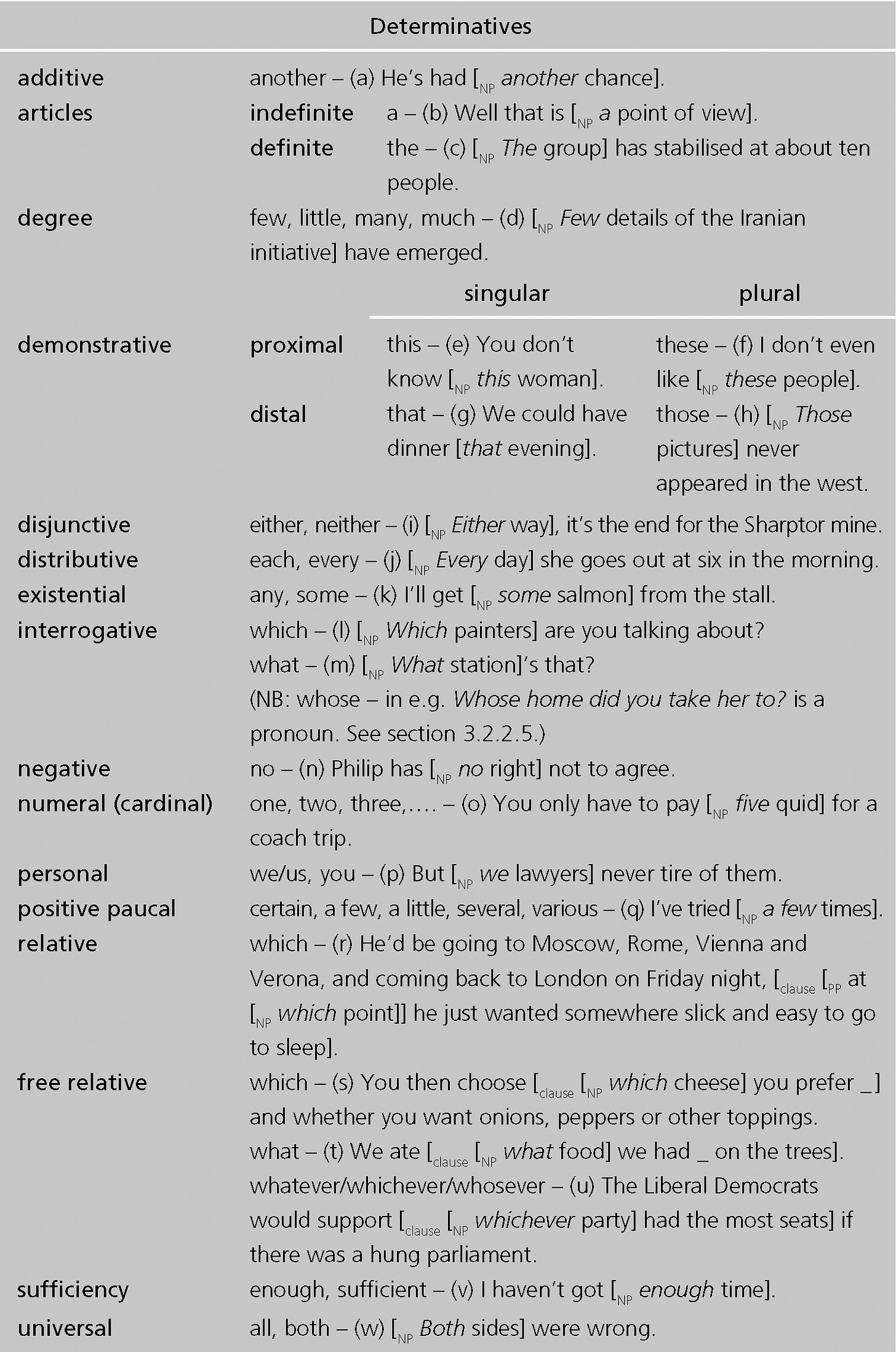

A determinative is a word that is typically placed at the beginning of a noun phrase, and can be said to limit the reference of the noun that it goes with. Determinatives can express a range of meanings, such as ‘indefiniteness’, ‘definiteness’, ‘proximity’, ‘remoteness’, ‘number’, ‘gender’, and ‘quantification’.

You are probably familiar with the words a and the, and the labels indefinite article and definite article. As I mentioned in my post on Parsing these two words are now subsumed into the wider class of determinatives, as are a host of other items.

Let’s look at some examples:

He told me a story.

Here the speaker uses the determinative a within the noun phrase a story to introduce something new into the discourse, namely a story that has not been mentioned before. As we have seen, this is traditionally called the indefinite article.

Consider now what happens when we use the:

I liked the story.

This time, within the noun phrase the story we have the determinative the and the noun story. By using the determinative the, the speaker indicates to the hearer that the story is somehow known to both of them: it is a story they can both identify because in the preceding discourse context it has been mentioned before. You can see how the word the limits what the noun story can refer to: the speaker is not talking about any old story, but a story that was mentioned before. We say that the determinative the communicates ‘definiteness’.

Let’s look at a further example:

I like these green shoes.

Within the noun phrase these green shoes we distinguish three elements: the determinative these, the adjective green, and the noun shoes.

Here again the determinative communicates definiteness, but notice that this time it communicates an additional meaning, namely ‘proximity’: the shoes that the speaker is pointing at are identifiable and they are nearby.

It’s important to be aware that adjectives do something different than determinatives: they attribute (ascribe) a property to a noun. So in the noun phrase these green shoes, green attributes the property of ‘being green’ to the noun shoes. In most cases noun phrases contain only a single determinative, but adjectives are stackable: these dirty, green, ugly shoes. We will return to adjectives in a later post.

Which kind of elements are in the word class of determinatives? You can see an overview from my Oxford Modern English Grammar (2011: 59) below:

Let’s now return to the label determiner. As I said above, I use this label as a grammatical function label, so we can say that in the simple noun phrase these shoes the word these belongs to the word class of determinative, but carries the grammatical function of determiner. Remember from my post on Parsing that we can assign grammatical form labels and grammatical function labels to all elements in linguistic structures.

Now, here’s an interesting question: if a word like these is a determinative in the noun phrase these books, how do we classify this word when it occurs on its own, as in I really like these?

Different grammars will give you different answers.

One answer is to say that when a word like these occurs on its own, it is a pronoun, more specifically, a demonstrative pronoun. This is the solution I adopted in my own grammar, and is also found in Quirk et al. (1985: 372).

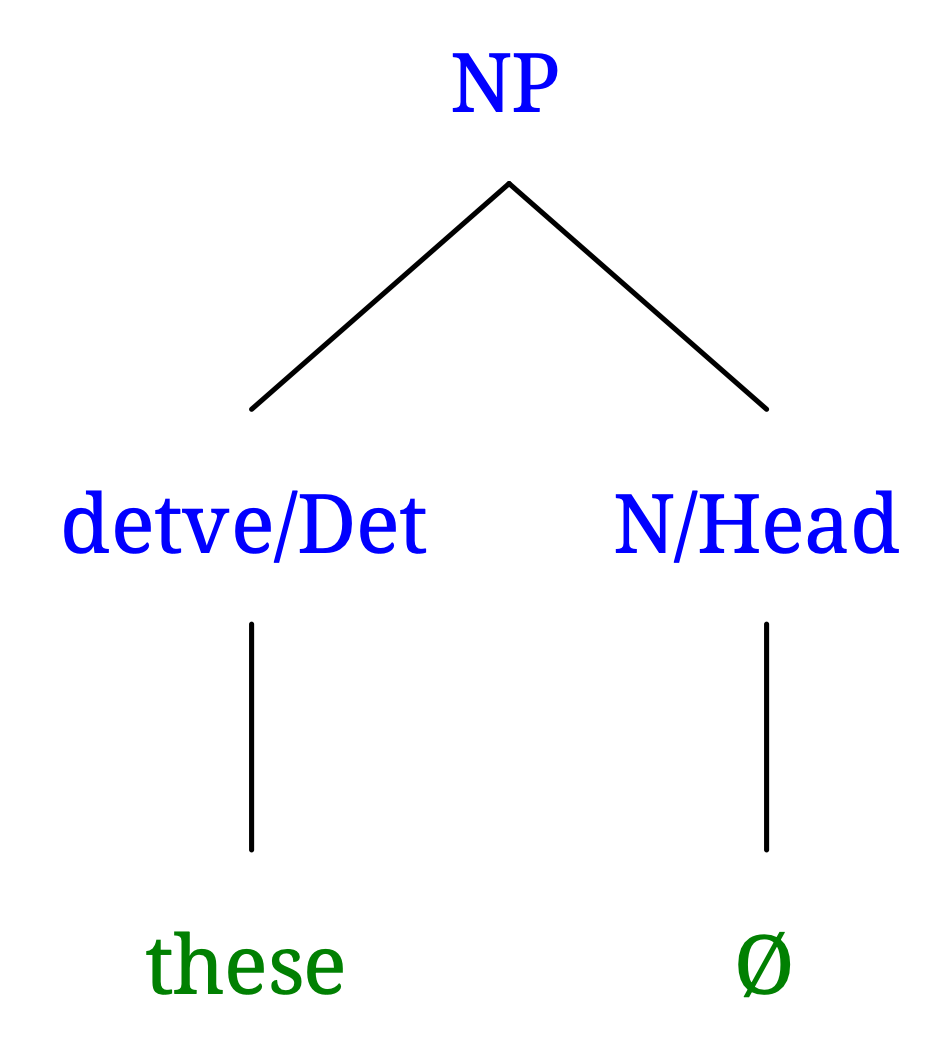

Another solution is to posit a zero Head inside the noun phrase to reflect the fact that when we say I like these there is a sense of something missing. For example, if we are pointing at some shoes, and say I like these, then we could say that the noun shoes is missing. In the tree below the symbol for ‘zero’ (Ø) is in the tree diagram indicating the missing Head:

Notice that in this analysis, where there is a missing Head, these is regarded as a determinative functioning as a Determiner.

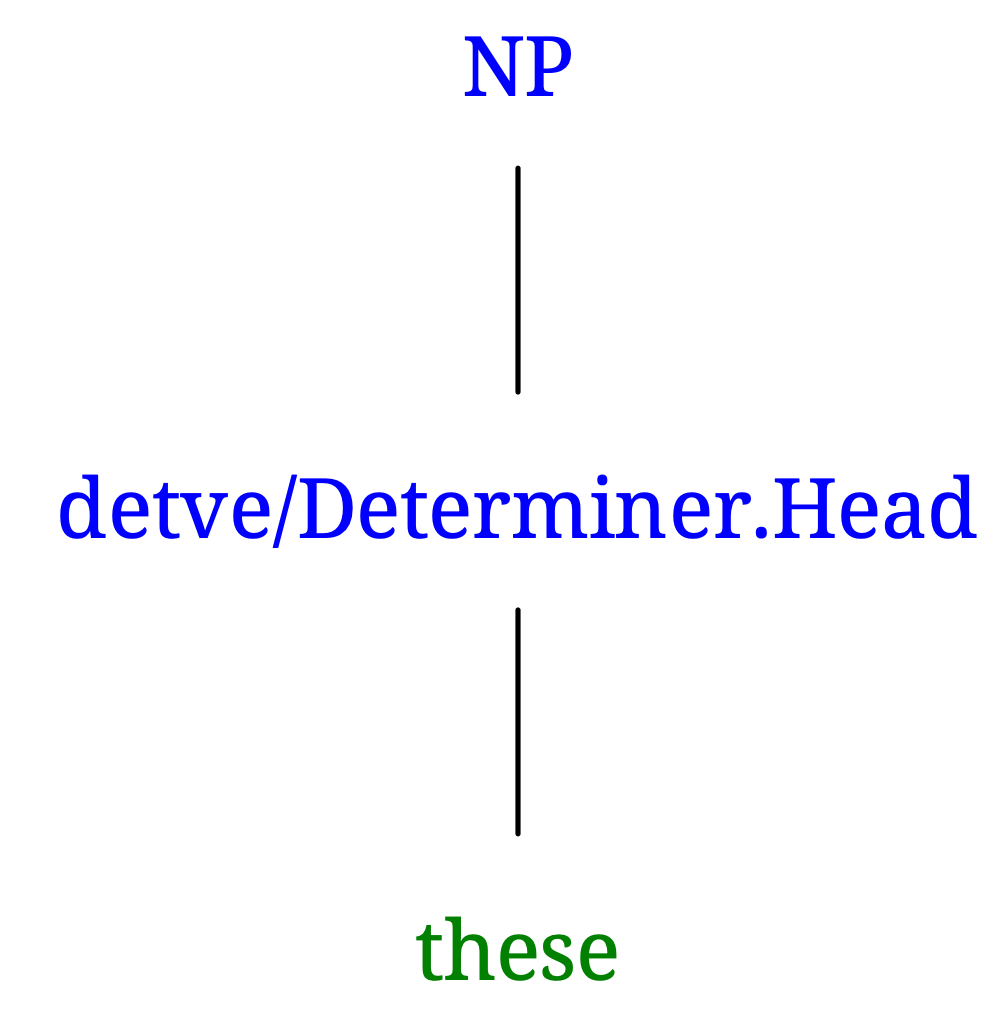

A third possible analysis is slightly more complicated. It is adopted in Huddleston and Pullum’s Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (2002: 412 f.).

In their analysis they argue that the word these on its own is a noun phrase, as in the two previous analyses. Within this NP these is a determinative, as in the zero Head analysis we just discussed. However, there is also an important innovation in their analysis. They say that these has a fused function, namely the function of Determiner-Head, and this is shown in the tree diagram below, with ‘Determiner.Head’ indicating the fused function.2

There is no zero Head here.

Fused functions merit a post of their own, so I will return to them later.

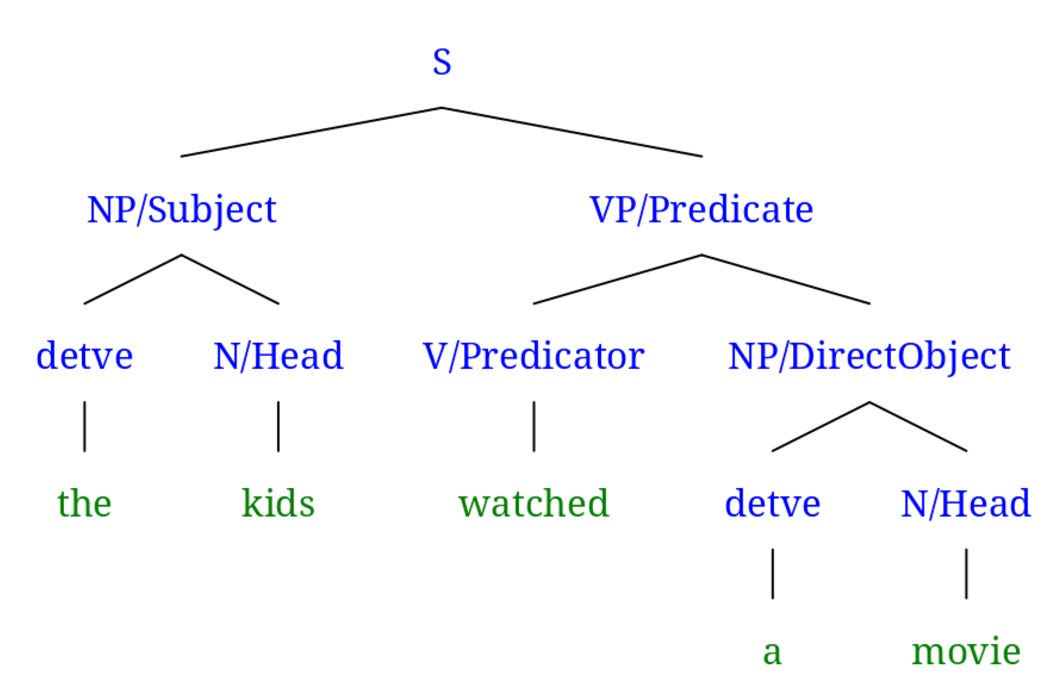

Finally, recall that in my post on Parsing I represented the structure of the simple sentence The kids watched a movie without there being a Determinative Phrase above the elements the and a:

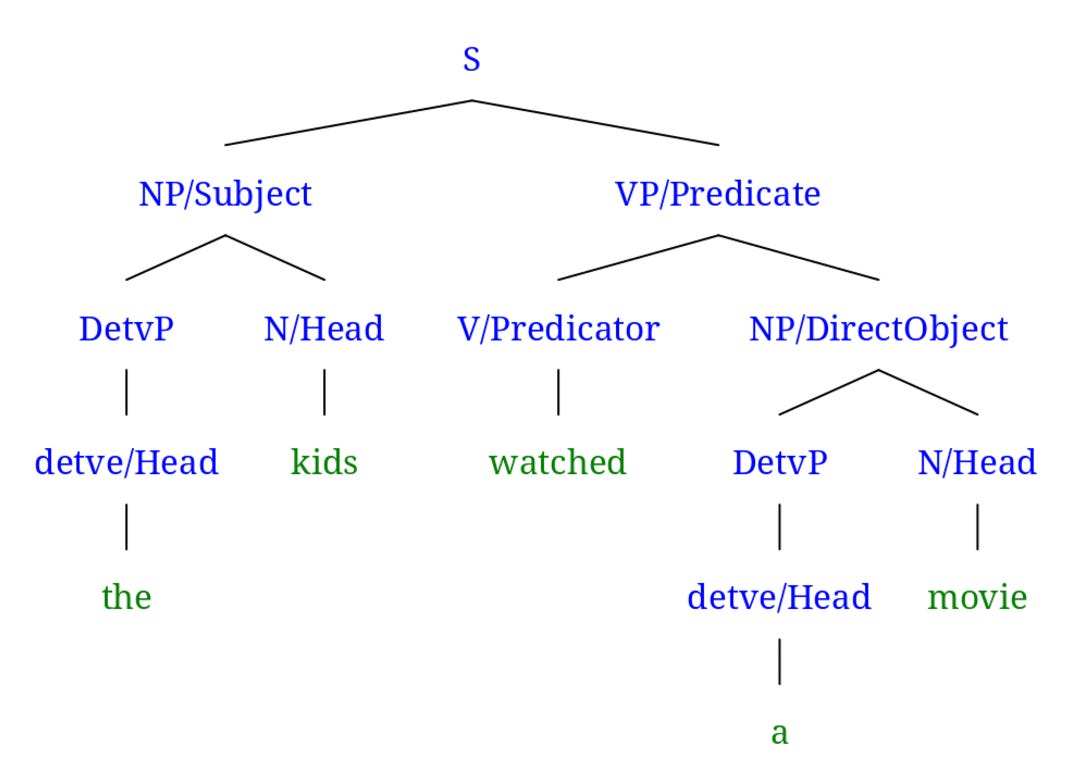

The eagle-eyed among you may have wondered why we have no phrase level above ‘determinative’. Indeed, there should be one. I left it out for expository reasons. In the amended tree diagram shown below we have Determinative Phrases (DetvP) immediately above the and a:3

Most of the time Determinative Phrases only contain a determinative as their Head, but they can contain also more elements, as in the noun phrase almost all shoes, where we regard almost all as a Determinative Phrase.

References

Aarts, Bas (2011) Oxford Modern English Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huddleston, Rodney and Geoffrey Pullum (2002) The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech and Jan Svartvik (1985) A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.

Further reading

Spinillo, Mariangela (2004) Reconceptualising the English determiner class. PhD thesis, University College London. Available online.

Quirk et al. (1985) reverse this practice: they use determiner as a word class label and determinative as a function label.

This tree structure has been simplified slightly, because Huddleston and Pullum assume an intermediate level of ‘Nom’ for ‘Nominal’, which I will return to in a later post.

In Chomskyan grammar we have Determiner Phrases (DP). These are different from the Determinative Phrases (DetvP) discussed here. A Chomskyan DP is a reconceptualised noun phrase: instead of saying that the Head of the NP the week is week, Chomkyan linguists (though interestingly: not Chomsky himself!) would argue that the Head is the.

"they can contain also more elements, as in the noun phrase almost all shoes, where we regard almost all as a Determinative Phrase."

Would you please tell me which determinative functions as the Head of the determinative phrase "almost all"?

Thanks in advance for your help.