Parsing

Grammatical form and grammatical function

In this post I will discuss parsing. Parsing is from the Latin word pars, which means 'part'.

So what exactly is parsing? Well, parsing is about pulling apart linguistic structures like sentences, clauses and phrases, in order to discover the individual parts, the bits and pieces, that make up those units, and how they function.

There are often different ways of analysing grammatical structures, depending on the grammatical framework that is adopted. My discussions will mostly be based on my Oxford Modern English Grammar (Oxford University Press, 2011). It's not necessary for you to know this framework already. I’ll explain it as we go along. Now and then I'll also talk a little bit about other frameworks of grammar, such as the framework developed by the American linguist Noam Chomsky.

Now, the thread in just about every post that I will write will make reference to a distinction that's made in grammar between grammatical form and grammatical function. It's not always explicitly made in grammar books, but it's very important for you to be aware what the difference between those notions two is.

Grammatical form refers to the building blocks of language, namely word classes (such as nouns, verbs, adjectives), phrases (noun phrases, adjective phrases, verb phrases, and so on) and clauses (main clauses, subordinate clauses, etc.), and the way in which these units are structured internally.

By contrast, grammatical function concerns grammatical relations: they indicate how a particular grammatical unit behaves (or functions) in a sentence in relation to other units, namely as Subject, Direct Object, Adjunct, and so on. (Notice that I’m spelling grammatical function labels with capital letters.)

English has eight word classes (or parts of speech), namely noun, determinative, adjective, verb, preposition, adverb, conjunction and interjection. Different frameworks may adopt a different set of classes, as we will see later, but this is the set I will be using on this Substack.

Elements from each of these word classes can form a phrase. So nouns are the central elements of noun phrases, which we define as a group of words in which the most important word is a noun, and we say that that the noun functions as the Head of the noun phrase.

We also have adjective phrases, adverb phrases, verb phrases, and prepositional phrases, etc., and I'll be looking at each of those in turn in later posts.

Also belonging to the notion of grammatical form are clauses. We have main clauses and subordinate clauses, and amongst those subordinate clauses, we have lots of different types, such as, for example, relative clauses and comparative clauses.

You'll already know most of the word classes I mentioned above , though one or two of them may be less familiar to you, such as the class of determinatives. In modern linguistics this word class includes words like a and the, which may be more familiar to you as the indefinite article and definite article, but also for example this, that, these and those. I take a closer look at determinatives in this post.

What about grammatical functions? Grammatical functions are grammatical relations. They indicate how grammatical units — we call them constituents in linguistics — behave or function in a sentence in relation to other units in the sentence. So here we are talking about notions such as Subject, Direct Object, Indirect Object, Predicative Complement and Adjunct, and sometimes also Modifier and Complement. We'll be looking at each of these functions in later posts.

Pulling apart sentences is what makes grammar fun. Let’s look at an example of how we can analyse the simple sentenceThe kids watched a movie. How do we analyze this sentence grammatically? How do we pull it apart? This particular sentence is quite straightforward, but, as we will see, there are lots of other constructions that pose grammatical puzzles.

So the sentence we have here is The kids watched a movie. First of all, it's obvious that you can't jumble up the words in this sentence at random. So you can't say *movie watched kids the a. That's not a possible sentence in English. We call it an ungrammatical sentence , and it’s a convention in linguistics that we indicate this by adding an asterisk to it.

However, we can move things around a little bit. So we can say, A movie, the kids watched, to highlight the noun phrase, a movie. This process of fronting is called topicalisation. It’s a very common way of drawing attention to a particular unit in the sentence, as we will see in a later post.

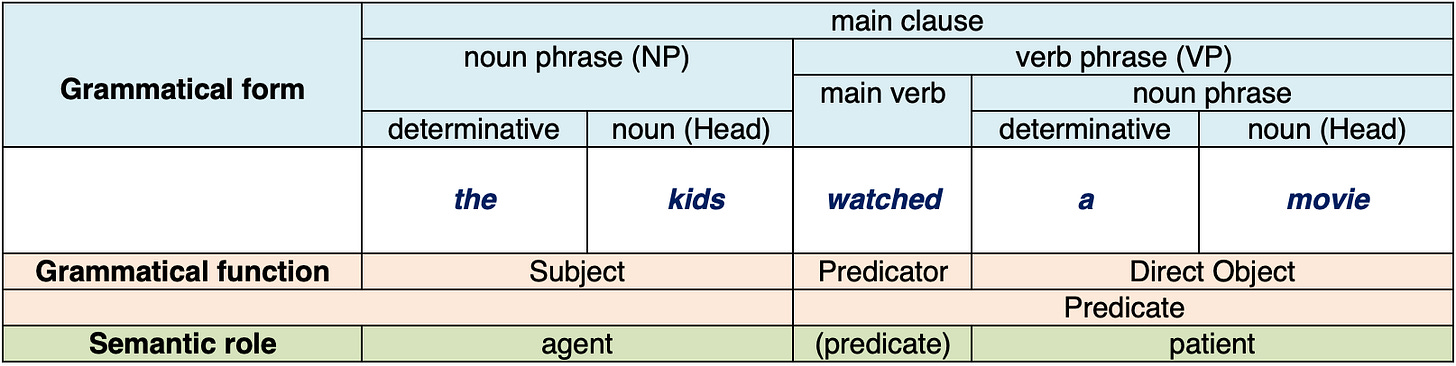

Let’s analyse this sentence by using a box diagram as shown below.

Here you see the sentence The kids watched a movie in the centre white portion. The blue portion of this diagram displays grammatical form labels. Each of the words of this sentences belongs to a word class, to a grammatical category. So we say the word the belongs to the word class of determinative that I mentioned earlier, and kids belongs to the word class of noun. Watched is a verb, a is another determinative, and movie is another noun.

A really important principle of grammatical analysis is that we assign words to word classes on the basis of their grammatical characteristics and company that they keep. For example, we say that kids is a noun because it has a plural form, and is preceded by the.

The units the kids and a movie are noun phrases, as discussed earlier.

We have another kind of phrase in this sentence, namely a verb phrase, which consists of the main verbwatched combined with the noun phrase a movie, as the diagram shows. An interesting question is why verb phrases are structured this way. I’ll discuss this in a later post.

We now come to the level of grammatical function, which is shown in the pale orange section of this box diagram. Here we see that the noun phrase the kids has the grammatical function of Subject. In a provisional way we can define Subjects as units that refer to an animate entity (e.g. a person or animal) that carries out an action, in this case ‘watching’. We’ll need to define Subjects more precisely later — in a grammatical way — but for now we will say that the Subject expresses the agent of whatever action is expressed by the verb.

Next we say that the noun phrase a movie functions as the Direct Object of this sentence. We can ask ‘What are the kids watching?’ The answer is a movie. From a semantic (meaning) point of view the phrase a movie expresses the patient (or undergoer) of the action expressed by the verb. (This is a linguistic concept, and has nothing to do with the everyday sense of that word.)

Agent and patient are semantic roles which are shown in the green section of the diagram.

We also assign a function to the verb watched. Here we use the label Predicator. This function is always performed by a verb which expresses what's going on in the sentence, in this case ‘watching’.

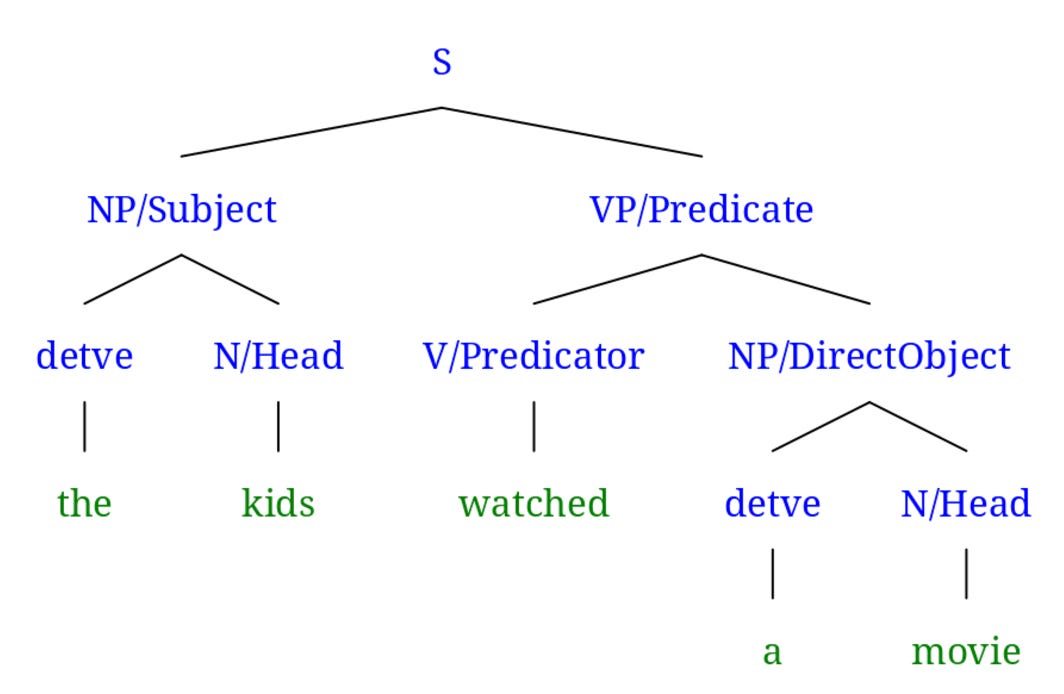

There is another way in which we can visualize the structure of our sentence The kids watched a movie. And this is done in a so-called tree diagram:

This is a graphical representation of the structure of that sentence. At the top of that tree diagram we have the label 'S' for sentence. And then you see two branches: one goes to the left, and the other to the right. (This is why it's called a tree diagram, because it has branches.)

On the left branch, you can see the noun phrase (abbreviated as ‘NP’) the kids, which has a label for grammatical function, namely Subject. This noun phrase consists of two parts, as we saw in the box diagram, namely a determinative, abbreviated as detve, and then the noun kids, which functions as the Head of this NP.

On the top-most right branch of this tree diagram, we see a verb phrase (VP), which functions as the Predicate in the sentence. The verb phrase itself branches into the verb watched, which functions as Predicator and the noun phrase a movie, which functions as the Direct Object (DO).

Notice that the notions of Predicate and Predicator sound similar, but they mean something very different: the Predicate in a sentence is the function we assign to the verb phrase, whereas Predicator is the function label we assign to verbs.

Next, the noun phrase that functions as Direct Object consists of a determinative a and the noun movie, which in turn functions as the Head of that noun phrase.

In future posts I will be looking at structures which have generated discussion in the grammatical literature because they pose puzzles, or that are interesting in some other way for students of English grammar.

Note: are you a speaker of Dutch? Have a look at redekundig.nl, which will analyse any sentence you enter on the website formally (taalkundig) and functionally (redekundig).