In my first post on this Substack I made a distinction between grammatical form and grammatical function:

The former refers to the building blocks of language, namely word classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.), phrases (noun phrase, adjective phrase, verb phrase, etc.) and clauses (main clause, subordinate clause, and so on), and the way in which these units are structured internally.

By contrast, grammatical functions are grammatical relations: they indicate how a particular grammatical unit behaves (or functions) in a sentence vis-à-vis other units, namely as Subject, Direct Object, Adjunct, Predicative Complement, etc. (Notice that I’m spelling grammatical function labels with capital letters.)

Here I want to say a little bit more about these concepts.

With regard to grammatical form, we can say that this concerns the word class labels we apply to the various elements that clauses are made up of. In my post on the word many I asked: which word class label do we assign this lexical item to? My answer was: adjective, based on the way this word behaves (or ‘distributes’) in different structures.

In the sentence The journalist opened a can of worms we distinguish the various word classes that the words are assigned to, namely determinative, noun, verb and preposition, as well as the phrases we find here: noun phrase, verb phrase and prepositional phrase.

But what about the grammatical functions?

As you can see, I characterised grammatical functions as grammatical relations. What does that mean? Before I answer that question, let’s take a look at the syntactic analysis of the sentence above.

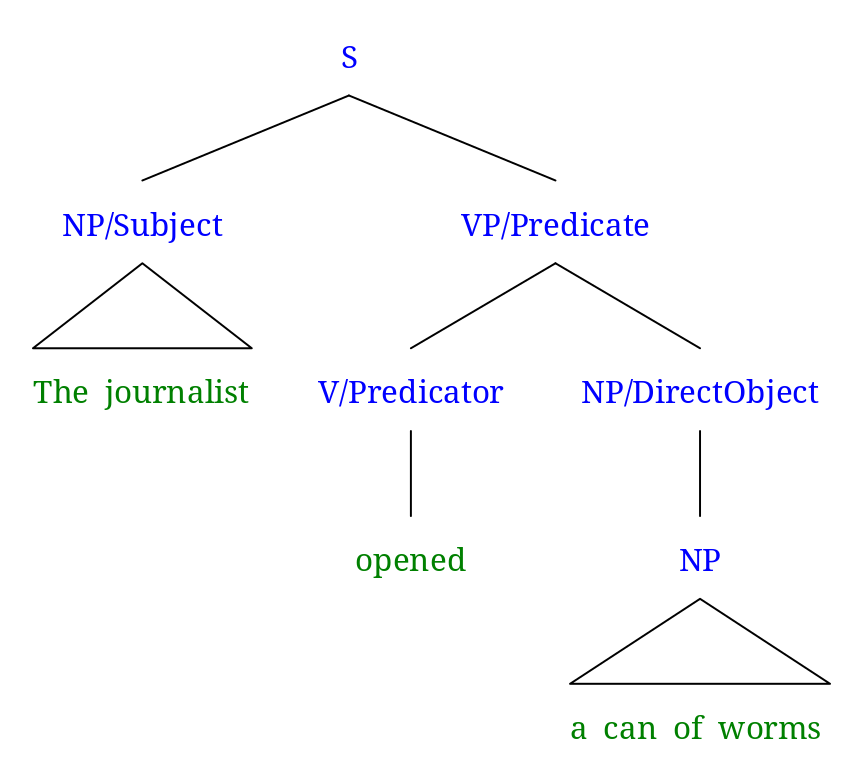

As we saw in my post on parsing, in this sentence the noun phrase the journalist functions as the Subject of the sentence, the NP a can of worms functions as the Direct Object, and additionally we assign the function label Predicator to the verb, and Predicate to the VP. Here’s the tree diagram of this simple sentence:

Now here’s the important point about grammatical relations. When a unit is assigned a function label such as Subject, Direct Object, etc., that unit is always the Subject of something or Direct Object of something, and that ‘something’ is typically a clause (not always, as we will see in a later post). So in our example sentence above the noun phrase the journalist is the Subject of the clause, and a can of worms is the Direct Object of the clause. It is in this sense that grammatical functions are relational.1

Grammatical relations figure more or less prominently in different pedagogical and theoretical frameworks of grammar.

In English Language Teaching frameworks the distinction between grammatical form and grammatical function is often neglected, or not made clear.

Here in the UK, the grammar specifications for the National Curriculum, while introducing three functional notions, namely Subject, Object and Adverbial, do not make clear that these are grammatical relations.2 Take a look at how the concepts of Subject and Object are defined in the NC Glossary:

The definitions are in terms of meaning and grammatical behaviour, but no reference is made to the fact that these are functional notions (though note the wording ‘acting as object’).

Let’s now look at the treatment of grammatical functions in two theoretical frameworks.

In Generative Grammar, a theory of language developed by the American linguist Noam Chomsky, grammatical functions do not play a very prominent role in explaining grammatical analysis. Indeed, if you look at recent textbooks on generative approaches to syntax, grammatical functions are often not defined, even though they are nonetheless mentioned. The reason for this is that in Generative Grammar grammatical functions are considered derivative notions, not primitive notions. What is meant by this is that grammatical functions do not need to be characterised as separate concepts. They can be read from tree diagrams. So in the tree diagram above, we can say that the Subject of the sentence is the first noun phrase we come across under the ‘S’-node. Put technically: it is the first noun phrase that is immediately dominated by ‘S’. And the Direct Object is the first noun phrase we come across under the VP-node. Grammatical functions can thus be defined configurationally.3

It’s another story for the Lexical-Functional Grammar framework (LFG). Here grammatical functions do play an important role, and they are linked to semantic roles such as agent and patient (called θ-roles or theta roles). Thus in Börjars, Nordlinger and Sadler (2019: 14) we read:

A fundamental property of LFG is that grammatical functions (GFs) are key concepts. They are not quite primitives; … they are derived … from the semantics of the predicate, but importantly they are not derived from their structural position, as they are in some other approaches to syntactic analysis.

In a later passage (ibid.: 179) they say:

… even though there is no one-to-one relation between θ-roles and grammatical relations, it is the case that there are general patterns and principles of mapping between θ-roles and grammatical functions within languages, and cross-linguistically. For example, in English and many other languages of the world, if a predicate requires an Agent argument and a Patient argument, then normally the Agent will be the subject and the Patient will be the object in a canonical mapping.

As in LFG, on this Substack I will regard grammatical categories and functions as crucial for a full understanding of how grammar works. In later posts I will discuss the various grammatical functions that we need to distinguish in English, namely Subject, Direct Object, Indirect Object, Predicative Complement and Adjunct, along with Complement and Modifier, in more detail. These functions will principally be defined with reference to syntactic structure, though semantics will naturally also play a role.

References

Börjars, Kersti, Rachel Nordlinger and Louisa Sadler (2019) Lexical-Functional Grammar: an Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The National Curriculum Glossary can be found here.

In a looser sense, in the example sentence we can also say that a can of words is the Direct Object of the verb, but strictly speaking it is a clause-level function

Complement and Modifier are not statutory terms in the NC.

In his book The Syntactic Phenomena of English (second edition, 1998, University of Chicago Press) James McCawley writes: ‘[I]t will be suggested that the existence of a plausible scheme of sentence understanding whose mechanisms crucially depend on grammatical relations such as “subject’’ and “direct object” provides some support for a conception of syntactic structure such as that of relational grammar (Perlmutter 1983), in which such relations are integral parts of syntactic structures and not (as they are for most transformational grammarians) merely parts of an informal meta-language for talking about syntactic structures that those relations are not considered to be parts of.’ (p.9)

Hi Bas, could you please suggest some materials if I want to know more about “derived notions” and “primitive notions”? Will the LFG textbook be useful? Thank you!