A while ago I wrote a piece on my Grammarianism blog about the use of the label adjective clause in the Australian curriculum.

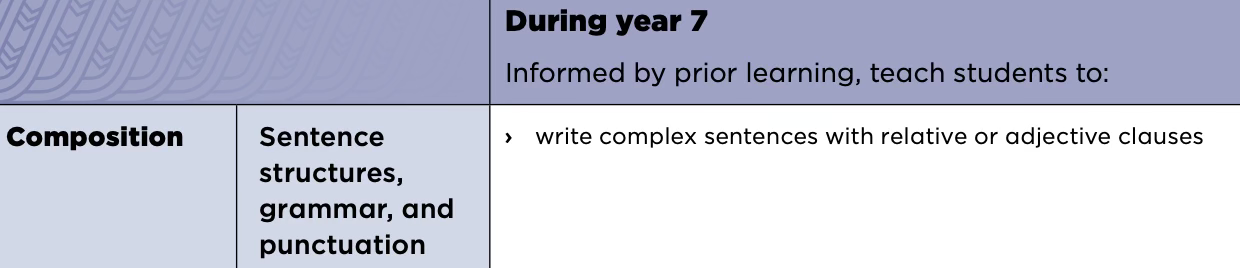

Much to my surprise — and dismay — the label adjective clause is now also included in the Draft New Zealand Curriculum for years 7-13:*

I bemoaned the use of the label adjective clause, as it makes absolutely no sense for any grammatical description to refer to the italicised portion of the example below, quoted in the NSW curriculum, as an adjective clause:

Rice paper rolls, which most people love, are usually healthy.

As I noted in the earlier blog post:

[T]he label ‘adjective clause’ fundamentally confuses grammatical form and grammatical function. The clause which most people love in the example above functions grammatically as a Modifier, and presumably it is called an ‘adjectival clause’ because adjectives can also have this function when they are placed in front of nouns. However, that’s where the resemblance ends. A relative clause does not carry any of the other typical defining characteristics of adjectives (e.g. comparative and superlative forms, being able to be modified by very, appearing in attributive and predicative position, etc.), so claiming that the clause in question is ‘adjectival’ is misleading and will confuse many teachers and students.

Where does the label adjective clause come from?

The Oxford English Dictionary has four citations, with 1834 as its first use (s.v. adjective clause):

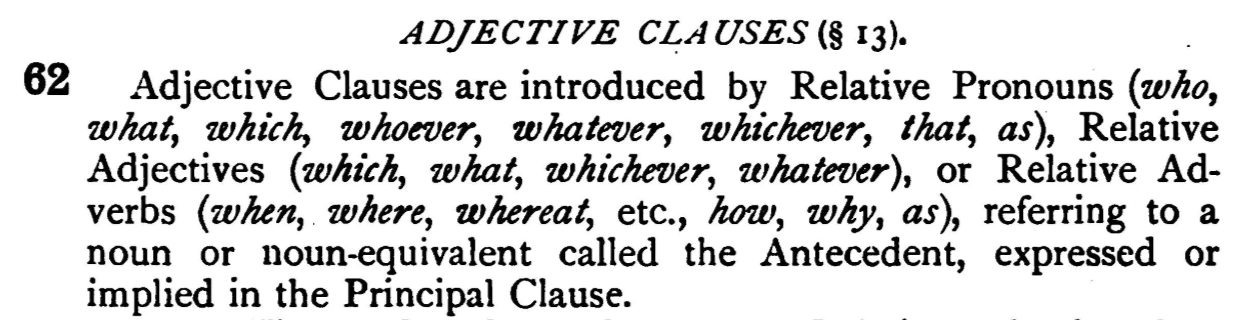

All these citations are all problematic in their own way. I won’t look at all the examples, but will focus on the third one, from Onions’ An advanced English syntax (1904: 70ff.). Here it is in full:

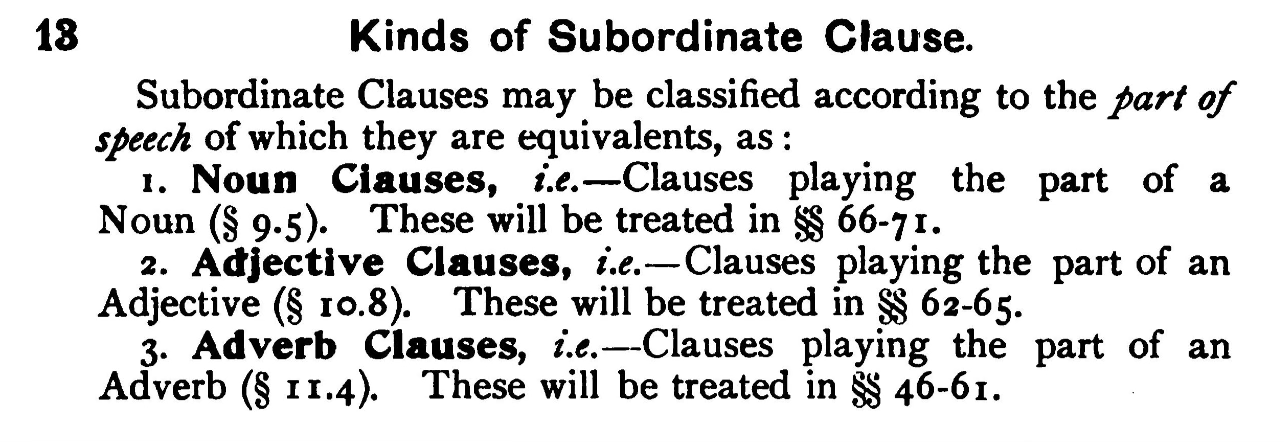

Adjective clauses are one type of subordinate clause among three (1904: 15):

Onions’ noun clauses are called nominal clauses in Quirk et al. (1985) and content clauses in Huddleston and Pullum et al. (2002). Adverb clauses are subordinate clauses that are introduced by subordinating conjunctions, such as although, because, since, when, while, etc. in Quirk et al. (1985). They function as Adverbial (or Adjunct if you prefer that terminology). The analysis is very different in Huddleston and Pullum et al. (2002) who regard the subordinating conjunctions mentioned above as prepositions, but that’s a whole different story for another day!

What about adjective clauses? Onions defines these as “playing the part of an Adjective”. He does not give any examples, but clearly what is intended is the notion of relative clause. In fact, oddly, Onions uses that very label in his section 63b (and onwards; 1904: 71ff.), where suddenly he drops the label adjective clause!

Regrettably, perhaps it’s Onions’ legacy that the label adjective clause has been widely adopted, because it is omnipresent on the internet, including on popular websites such as Grammarly, Grammar Monster, and even on academic support sites.

Incidentally, the same confusion of form and function happens when grammar sources label a word like student in student job as an adjective, or as ‘a noun playing the role of an adjective’, or some such wording. This is wrong-headed. We need to recognise that, like adjectives, nouns can modify nouns, but just because they share this feature with adjectives does not mean that they should be analysed in the same way. What we need to say is that student in student job is a noun (or more precisely, a noun phrase) that functions as a Modifier in a noun phrase.

Does all this matter?

Yes, it does. Labels like adjective clause will cause a huge amount of confusion for anyone studying English grammar, because in almost all examples that you come across in books and on the internet there is nothing adjectival about adjective clauses, and, as noted above, the notion of adjective clause confuses grammatical form and grammatical function.

Students in Australian and New Zealand schools can be forgiven for being confused — and perhaps disillusioned — about the study of grammar when the curricula in their countries use outdated and ill-conceived terminology.

References

Huddleston, Rodney, Geoffrey Pullum et al. (2002) The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Onions, C.T. (1904) An advanced English syntax. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech and Jan Svartvik (1985) A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.

* “The New Zealand Curriculum is the official document that sets the direction for teaching, learning, and assessment in all English medium state and state-integrated schools in New Zealand. It guides schools on what they should teach and how they should teach it, with the goal of fostering lifelong learners who are confident, creative, connected, and actively involved.”

I’m not so sure that “it’s Onions’ legacy that the label adjective clause has been widely adopted.” Rather, I suspect it is the legacy of the authors of the OED’s previous example. Reed and Kellogg also use "adjective clause" to mean ‘relative clause’ and, in addition to being relatively early users of this term in this way, were very influential in grammar pedagogy (at least in the U.S.). Reed and Kellogg’s textbooks have been widely used in English language arts teacher training programs. Indeed, their sentence diagramming system is still included in a textbook that I am expected to use for my course on English linguistics for future teachers (though the authors include them alongside phrase structure trees and imply that they are only included to appease traditionalists).

While I agree that “adjective clause” has the potential to confuse students, it isn’t the worst choice I’ve seen in pedagogical grammars, sadly. For instance, I know of at least one that classifies all prepositional phrases as kinds of adverb phrases because they “function adverbially.” The same text elsewhere claims that phrases are headed by words of a matching part of speech. Yet it never explains how a prepositional phrase could be a kind of adverb phrase despite lacking an adverb as a head.

This is a cogent essay--and is especially useful for me because I sometimes get caught up in function and have to reconsider when describing things in terms of form. I've definitely been guilty of describing relative clauses as adjectival or adjective-like when describing how they act in sentences, though I don't think I've ever gone so far as to call them adjective clauses.

I think there's a tendency for educational materials to be simplified in the name of "plain language." Words like "adjectivally" get edited out for sounding too academic or abstract for a young audience, and you end up with things like "adjective clause."

That doesn't explain what's going on with Onions, though. I briefly looked at Curme on this issue but found his discussion of adjective clauses a bit murky. Your explanation provides clarity.

I'm eager to hear what you have to say about Huddleston and Pullum et el. on subordinating conjunctions as prepositions!