Grammar was reintroduced into the National Curriculum (NC) for UK primary schools in the late 1980s, having disappeared from the curriculum for quite a long time. The curriculum was updated in 2014. Children are required to learn the basics of grammar, including terminology such as 'noun', 'adverb', 'subject', etc., and take tests at Key Stages 1 and 2.

As a linguist I'm very pleased that grammar is back in the curriculum for the reasons I discussed in this post, so I won't repeat what I've said before. The current post is prompted by a flood of negative publicity in the UK media about grammar in schools, more specifically the tests taken in years 2 and 6. Here's an example from the Guardian:

Quite a few commentators are pointing out that the tests are too hard, pointless and inappropriate for school children. Others have noted that grammar teaching is no more than 'the naming of parts', and does not help children to write well and imaginatively. Teachers have expressed frustration with the tests, especially because they often already feel unsure about their subject knowledge of grammar. Many weren't taught much grammar in their teacher training.

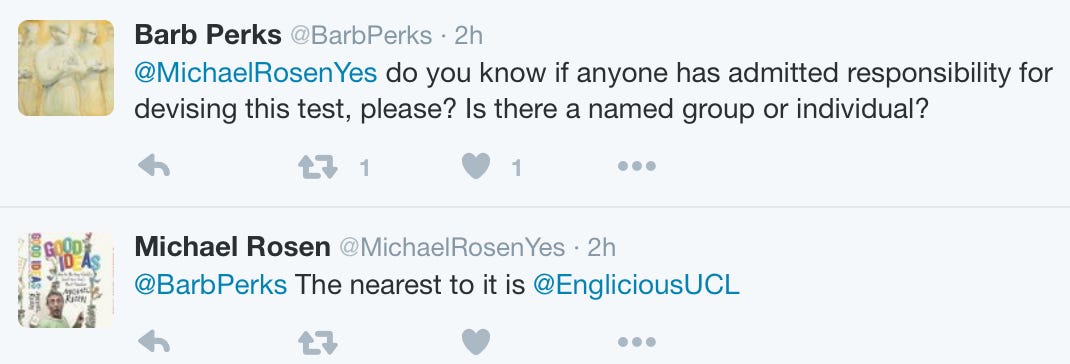

The Englicious project has been mentioned in some of the discussions on Twitter, especially by Michael Rosen. More about that below.

In what follows I'll try to address some of the points made in the media about grammar in schools, testing and the role of Englicious.

At the outset I would like to make the following very clear: Englicious is an independent initiative to help teachers teach grammar in schools. It's a free resource created by an enthusiastic team of people at UCL. The site offers subject knowledge, lesson plans, videos, an extensive glossary and tons of materials for children to use in the classroom or at home. Our aim is for kids to enjoy learning about the language they use every day, to understand how it works, and to use it more effectively both in their formal and creative writing. We hope that we can make a difference in improving children's literacy.

Here are some questions and answers:

Q: Do you think that the people who have pointed out problems with the curriculum are wrong?

A: No, I agree with them. There are certainly problems with the curriculum, and the recent furore over exclamations is a case in point. Such was the confusion over this that the Secretary for Education published a letter of clarification in a newspaper, a sure indication that something was wrong. I agree that learning about how exclamations are grammatically defined as a sentence pattern that has either the word 'what' or 'how' in it is perhaps too difficult for children, and arguably not something they need to know at age 6-7. It must be said, though, that there was also a lot of disinformation about this, because many commentators claimed (and others parroted) that children can now only use exclamations marks after sentences that begin with 'what' or 'how', and this is simply not what the NC says. But now I'm beginning to sound like a DfE civil servant, which leads me to the following question.

Q: Some people have suggested that Englicious is responsible for the grammar tests in schools. Is it true that Englicious is responsible for devising the test? Is Englicious a mouthpiece for the government?

Here are some examples of tweets posted by Michael Rosen:

A: No, neither of these is true. The tests are the responsibility of the Standards and Testing Agency at the DfE. As noted above, Englicious is brought to you by UCL, a university whose members have a mind of their own, thanks very much, ever since Thomas Arnold referred to us as that "Godless institution in Gower Street". We do, however, have a passion for grammar and believe in the benefits it can bring for school children. We're in favour of good and enjoyable grammar teaching in schools. Tweets like Rosen's are unfortunate and give the wrong impression of what we are trying to do.

Q: But hold on, I have heard that one of the UCL Englicious team is involved with the SPaG tests. Is that true?

A: Yes, that's true. I'm a member of a DfE Test Review Group of teachers, literacy advisors, and academic experts who scrutinise the tests before they are used in schools. Draft tests are rigorously and critically examined and discussed, and rejected if they are not fit for purpose. I have also been involved to some degree in giving shape to the NC Glossary. At all times, when taking part in meetings at the DfE, I'm a critical participant and would like to think that my presence helps avoid the appearance of unreasonable, silly or undoable questions on the test.

Q: What is your view of the tests?

A: The tests are designed to test the curriculum, and as such they are part of how education works. The tests are by no means perfect and subject to improvement, which is why I have agreed to advise the government. I hope that over time the curriculum and the tests can be improved. This is not the place to discuss the efficacy of the tests, their usefulness or the politics surrounding them. There are valid questions to be asked about any of those issues.

Q: The grammar that is used in the NC is full of holes and linguists can't agree on the terminology that is used.

The tests are based on a particular model of grammar which was designed by linguists as a useful 'school grammar'. It is important to have a model because it eliminates (or at least reduces) confusion and the problem of teachers using terminology that is not fit for purpose, such as possessive adjective, or connective. In linguistics, as in any other area of study, there are differences of opinion on how we analyse certain phenomena. This situation is no different from any other discipline. For example, historians will disagree about the significance of historical events or individuals. Andrew Roberts recently wrote a biography of Napoleon, the upshot of which is that he was a misunderstood military genius. For others he was a war-mongering tinpot dictator, responsible for the deaths of thousands. Do we stop teaching history because of these disagreements? Or think of the multiple ways in which we can interpret the character of Hamlet. Do we stop teaching literature because of that?

The criticism levelled by Michael Rosen at the grammar model used in the NC is therefore misguided. He writes on his blog: "Please, please, please don't be kidded into thinking that the stuff the DfE are dishing up as 'grammar' IS grammar." I agree. As noted above, the grammar used in the NC is a particular model of grammar, agreed by a group of linguists. It is by no means a perfect model, but I think most people would agree that you do need a model to teach grammar. Most subjects use some kind of model and and associated terminology. Compare the first passage below from Rosen's blog with my re-written version:

So, if I say, something is a 'conjunction' - all that tells us is that it con-joins two things. It doesn't tell me anything about the resultant meaning or why I would want to conjoin anything.

So, if I say, something is a 'metaphor' - all that tells us is that it compares two things. It doesn't tell me anything about the resultant meaning or why I would want to compare anything. Michael, would you wish to argue that nobody should teach school children about metaphors? Presumably not. Learning about conjunctions or metaphors is a first step towards understanding how and why they are used by authors in their writing, and once you've understood this you can use them yourself effectively in your own writing.

Q: What is your view of some of the test questions that have surfaced online?

A: Some of the test questions that have appeared online are taken from commercially published books that have been marketed to 'help' children practise for the tests. The problem with some of these books is that they have been written by people who don't know grammar well enough, or haven't looked at the NC teaching specifications and/or test framework. This has resulted in questions appearing in these books that would never appear in the tests, because the questions are wrong and have not been scrutinised by experts. Michael Rosen posted one such query in a recent blog post:

He then asks: "wouldn't both example 3 and 4 be subordinate clauses of time, both headed by subordinating conjunctions?" The answer is 'yes, both are indeed subordinate clauses'. Now, the problem here is not the NC, but the person who wrote this question, because they clearly don't know enough grammar to be writing practice books for school children. There's no problem with the grammar itself because in the NC both those clauses are subordinate clauses, and therefore this question would not appear on a test. Rosen goes on to ask "how is any teacher supposed to teach this so it makes sense? how is any child supposed to remember it? how is any parent supposed to know how to help a child to do it?" All good questions, but he fails to spot the real problem, which is that the government has not provided reliable resources to help teachers teach grammar. If teachers continue to turn to badly written books, or to use Google to help them with grammatical terminology, then confusion will ensue. I'm told that money was made available when the first NC came out to help teachers with their subject knowledge. This time round, there is no money available, which is causing many problems.

Q: What is your view of the NC Glossary?

The Glossary is an attempt to create some support for teachers with grammatical terminology. Again, nobody would claim that it is perfect, but the DfE is to be given some credit for consulting on this and listening to experts. The Glossary is, somewhat oddly perhaps, non-statutory, which means that not all the terminology in it needs to be taught in schools. The Englicious team has enhanced the Glossary to offer further explanations and support for teachers. It can be found here.

Q: What about subjunctives? Do kids really need to know about them?

No, they don't. As is by now well-known, linguists advised the DfE to remove the subjunctive from the NC. Michael Gove insisted that it remain(s) in the NC. My views on the subjunctive can be found here.

Q: Some parents and teachers have said that kids hate learning about grammar.

A: That's a real shame. Kids needn't have this kind of experience. We created Englicious to help teachers to make learning about grammar fun. This teacher agrees about the joys of learning about grammar:

A plea

I finish this blog post with a plea. There has understandably been some disquiet about the grammar tests in the media. Some of the problems signalled by commentators are indeed problems; others weren't really problems, but turned into easily gobbled-up, eye-catching tabloid-style headlines.

And here I turn to you, Michael Rosen. As a person who has enormous popularity and influence, why not channel your admirable, seemingly inexhaustible energy into working with Englicious and other stakeholders, who essentially want the same thing, namely to improve literacy, and instil in kids a joy for language and literature.

Postscript

I've realised that Michael Rosen is not interested in constructive dialogue. On Twitter he continues his cynical sniping. And my plea above fell on deaf ears, witness his blog response, which you can read here. I hope that readers will make up their own minds.